|

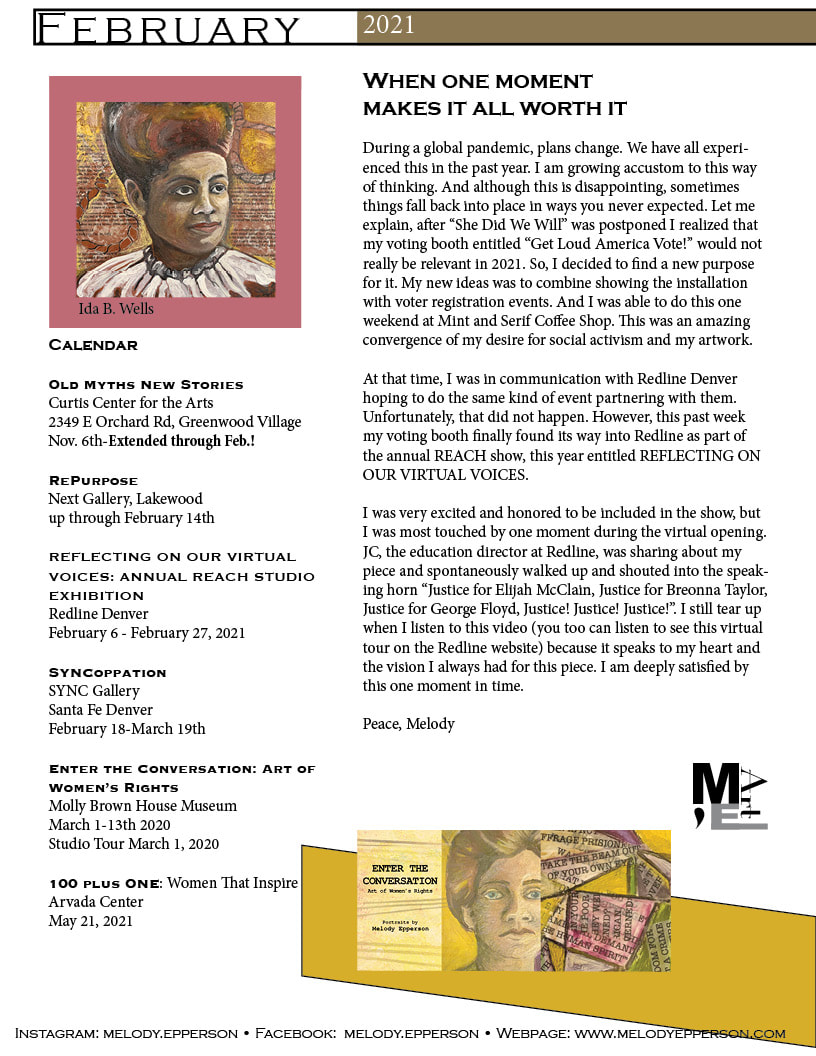

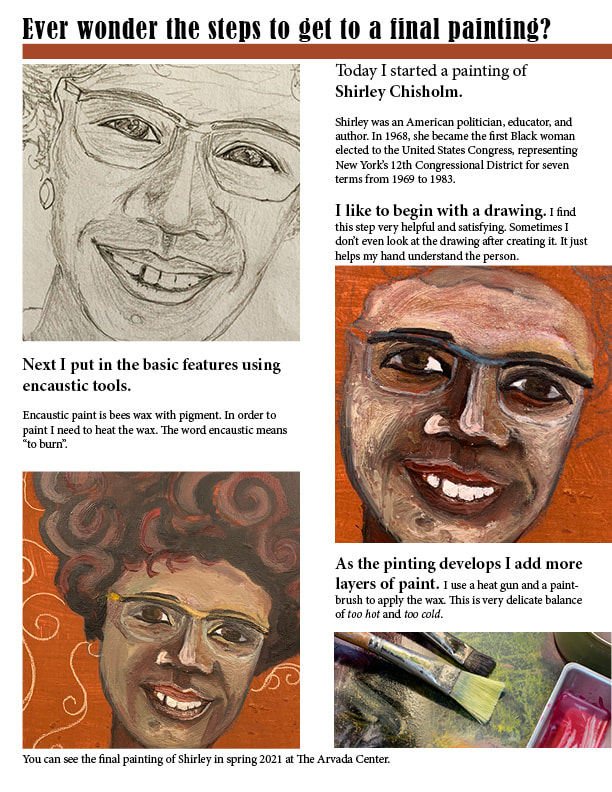

As an artist, I begin my process with research. I have many wonderful resources with stories of amazing women. Once I have researched the woman I am interested in painting, I look for an image of her. It is fun searching for these historic images. After I choose an image for inspiration, I make at several sketches. Now that I am ready to paint, I transfer a simple sketch on a piece of board that has been covered with Gesso. I use homemade gesso usually. Gesso is just a special kind of glue mixed with chalk or some other mineral that makes the encaustic paint stick a little better. However, you don’t have to use gesso with encaustic paints, which is what I use in my paintings. Painting with encaustic wax is very different than painting with oil or acrylic paints. Encaustic paint is made out of beeswax and resin. In order to get the encaustic paint onto the board I have to heat it up, I do this on a hotplate. The paint is hard like a very hard candle when I start. Once it melts, I have about 5 seconds to apply it to the board. But I use a heat gun in one hand to keep the paint warm longer. It takes a lot to practice to co-ordinate these two things at the same time. Another important tool I use is a heated pen-like tool. I use this to blend the paint and draw with the paint. Encaustic painting is a very ancient process of painting and very difficult to master. It has been around for thousands of years. Perhaps the best known of all encaustic work are the Fayum funeral portraits painted in the 1st through 3rd centuries A.D. by Greek painters in Egypt. In ancient times the artist would heat this horn-shaped pen in a fire. I am lucky that I only need to plug it in. Join me each week at the Molly Brown House museumI am thrilled that the Molly Brown House Museum will be posting a weekly series of my suffragist portraits on their social media sites. Each week for the next few months a painting and information on the suffragists will be posted. Follow on https://www.instagram.com/mollybrownhouse/ and https://www.facebook.com/mollybrownhousemuseum/

March 14th, 2020

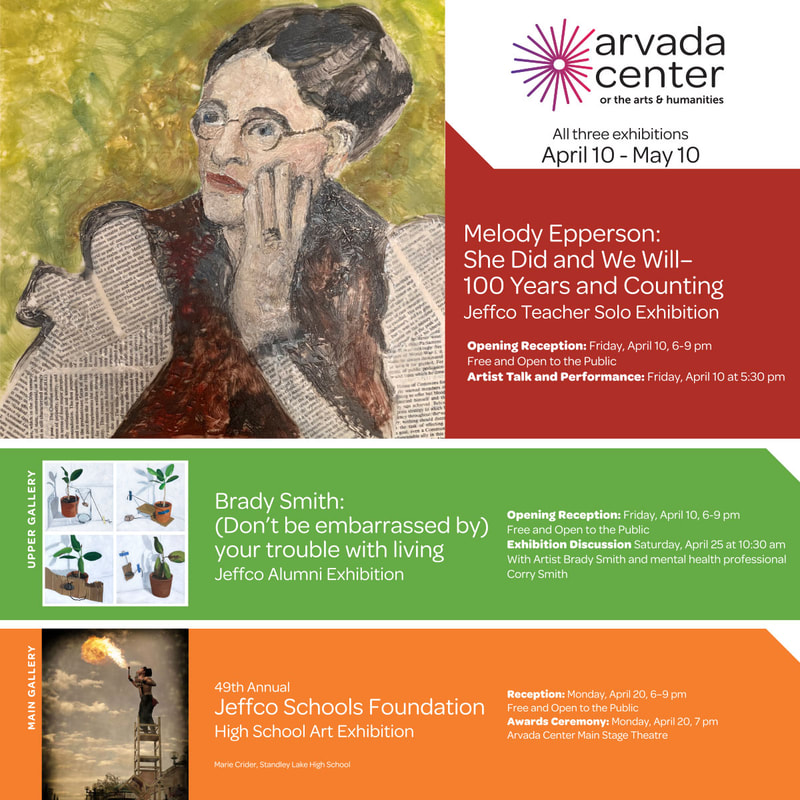

We are getting a lot of these kinds of notices the past few days, so you probably can anticipate what I have to say… Unfortunately, due to the COVID 19 virus, my show “She Did and We Will” at the Arvada Center, April 10, 2020, has been postponed ONE YEAR. Next April 2021, I will show either this work or some other body of work. The good news is, it was not cancelled, just postponed. And I get another year to develop this work, improve and refine my vision. (At this point I am not sure what I want to do. I may try to find another place or way to share this work in 2020) Obviously, I am disappointed, but I support doing whatever it takes to keep people healthy. So, stay healthy and I will keep you informed as to other shows that are ahead. Namaste, Melody Epperson |

MelodyWomen rock! You know it! I make art about it! Archives

February 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed